Tags

API, API Commons, APIs.io, Async API, IETF, OAS, RFC, specifications, Technology, WELL-KNOWN

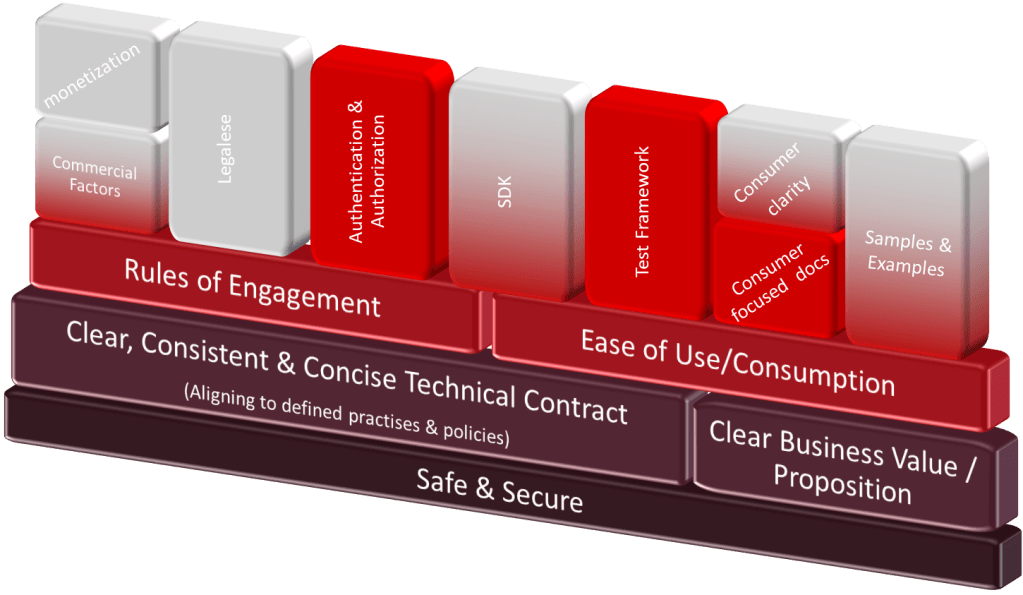

I have long said that APIs are more than just payload definitions. For public APIs or those being made available within large organisations, where discoverability and making it easy for APIs to be adopted are just as important to the definition of the API. API specification standards such as Open API Specification and Asynchronous API Specification have addressed some of the challenges, the specifications don’t address everything.

I’ve recently been working on the public API and integration strategy for a product, and revisiting this very point to ensure there is time for the wider needs.

There is good news in this area. The IANA-governed WELL-KNOWN path has been added to as a result of the IETF RFC 9727, which defines a way of structuring a list of defined APIs for the api-catalog path (e.g., https://www.example.com/.well-known/api-catalog).

The URI then returns a JSON-based payload using the relatively new media type of linkset (application/linkset+json), which is consists of an anchor to the actual API. Additional attributes (per IETF recommendations) can be supplied to reference metadata, such as the API specification. and other attributes made up of an href and a type. The RFC includes a set of suggested additional metadata references, which could cover details such as:

| Attribute Name | Description |

|---|---|

| service-doc | Link to the API specification document, such as the Open API Specification |

| status | Link to the endpoint providing status information the API, for example whether the service is currently available. |

| service-meta | Additional machine readable metadata that maybe needed. |

| availability | Details about the service availability, e.g. are there any SLAs/SLOs, when maintenance windows may occur etc |

| performance | Details of any rate limits imposed upon the API |

| usage | The provider of the api-catalog may wish to correlate requests to the /.well-known/api-catalog URI with subsequent requests to the API URIs listed in the catalog |

| current | Provide information about which services may be deprecated or no longer available. |

| Suggested additional attributes. |

Given this, the response data structure could look something like this:

{"linkset": [ { "anchor": "https://developer.example.com/apis/foo_api", "service-desc": [ { "href": "https://developer.example.com/apis/foo_api/spec", "type": "application/yaml" } ], "status": [ { "href": "https://developer.example.com/apis/foo_api/status", "type": "application/json" } ], "service-doc": [ { "href": "https://developer.example.com/apis/foo_api/doc", "type": "text/html" } ] }, [#... next API service]}This opens the door to referencing additional content that may not be available in the current API specifications (and for wrapping structural context around GraphQL APIs, which don’t have as good documentation semantics as OAS, for example). But, as we’ve mentioned, even OAS doesn’t provide an easy way to publish references to SDKs for example, which using the catalog could not be easily referenced. The question is: how do we identify these different building blocks? Here, apicommons.org can come to our rescue. Rather than provide a highly prescriptive specification like the OpenAPI Specification and others. It has reviewed the different standards and practices and identified the commonly needed resources, ranging from authentication details to versioning strategies. Each entry provides recommended tags or attributes to use, which map perfectly into the additional entries for the IETF 9727 linkset.

If you review all the aspects described in apicommons.org, you’ll note that the potential list of resources that you may wish to offer is extensive, and may not be best suited to all being in each catalog entry. This isn’t an issue. Alongside the API Commons site, there is another partner site, APIS.json. This offers a machine-readable API definition. It does not seek to compete with OAS, etc., or to disrupt or displace standards such as OAS; doing so would be a real uphill struggle, as it is too well adopted (to the point we’ve seen good alternatives such as API Blueprint, and RAML fall away to minimal or no advancement). APIs.json is a wrapper definition to the likes of OAS, providing a standardization of the elements identified by APICommons. So we could simplify our catalog to the mandatory API endpoint and a supporting reference to the API.json, which will bring all the resources mentioned together.

While these sights place a clear emphasis on JSON-centric APIs, nothing prevents much of this from being applied to non-JSON APIs (in fact, if you look at the spec for JSON.APIs, you’ll see references to technologies such as WADL and others). The only JSON restriction is that files must be defined in JSON or YAML.

Human-searchable API catalog

Until a few years ago, the Programmable Web website managed a curated catalog of APIs – and it was a fantastic resource, both for discovering potential third-party resources, but also ideas on how to best model your own API specifications, as the API Evangelist blogged that site has since closed its doors. With all the above efforts, there is clearly an opportunity to automate curation of public API services, which is much more viable. This is the direction APIs.io is taking: it is not crawling the web to collect API documents. However, given the support of a search engine and the WELL-KNOWN specification, it is certainly achievable and more a question of funding and, probably, investment in functionality to filter out poor or incomplete API specifications. Currently, to have an API integrated into the catalog, you must manually submit your APIs.json specification.

When using APIs.io, APIS.json, and API Commons, we should treat these resources with respect; they’re beautifully clean sites, knowledge-rich, with no advertising to fund them, and being paid for by the likes of Kin Lane (API Evangelist), Nicolas Grenier (Typeform Inc.), and Steven Willmott (Timewarp Labs).

You must be logged in to post a comment.